Riesz space

In mathematics a Riesz space, lattice-ordered vector space or vector lattice is an ordered vector space where the order structure is a lattice.

Riesz spaces are named after Frigyes Riesz who first defined them in his 1928 paper Sur la décomposition des opérations fonctionelles linéaires.

Riesz spaces have wide ranging applications. They are important in measure theory, in that important results are special cases of results for Riesz Spaces. E.g. the Radon-Nikodym theorem follows as a special case of the Freudenthal spectral theorem. Riesz spaces have also seen application in Mathematical economics through the work of Greek-American economist and mathematician Charalambos D. Aliprantis.

Contents |

Definition

A Riesz space E is defined to be a vector space endowed with a compatible ordered lattice structure. Specifically, every finite subset of E has a supremum and infimum.

Basic properties

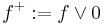

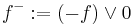

Every element f in E has unique positive and negative parts, written  and

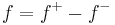

and  . Then it can be shown that,

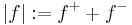

. Then it can be shown that,  and an absolute value can be defined by

and an absolute value can be defined by  . Every Riesz space is a distributive lattice and has the Riesz decomposition property

. Every Riesz space is a distributive lattice and has the Riesz decomposition property

Order convergence

There are a number of meaningful non-equivalent ways to define convergence of sequences or nets with respect to the order structure of a Riesz space. A sequence  in a Riesz space E is said to converge monotonely if it is a monotone decreasing (increasing) sequence and its infimum (supremum) x exists in E and denoted

in a Riesz space E is said to converge monotonely if it is a monotone decreasing (increasing) sequence and its infimum (supremum) x exists in E and denoted  (

( ).

).

A sequence  in a Riesz space E is said to converge in order to x if there exists a monotone converging sequence

in a Riesz space E is said to converge in order to x if there exists a monotone converging sequence  in E such that

in E such that  .

.

If u is a positive element a Riesz space E then a sequence  in E is said to converge u-uniformly to x for any

in E is said to converge u-uniformly to x for any  there exists an N such that

there exists an N such that  for all n>N.

for all n>N.

Subspaces

Being vector spaces, it is also interesting to consider subspaces of Riesz spaces. The extra structure provided by these spaces provide for distinct kinds of Riesz subspaces. The collection of each kind structure in a Riesz space (e.g. the collection of all Ideals) forms a distributive lattice.

Ideals

A vector subspace I of a Riesz space E is called an ideal if it is solid, meaning if for any element f in I and any g in E, |g| ≤ |f| implies that g is actually in I. The intersection of an arbitrary collection of ideals is again an ideal, which allows for the definition of a smallest ideal containing some non-empty subset A of E, and is called the ideal generated by A. An Ideal generated by a singleton is called a principle ideal.

Bands and  -Ideals

-Ideals

A band B in a Riesz space E is defined to be an ideal with the extra property, that for any element f in E for which its absolute value |f| is the supremum of an arbitrary subset of positive elements in B, that f is actually in B.  -Ideals are defined similarly, with the words 'arbitrary subset' replaced with 'countable subset'. Clearly every band is a

-Ideals are defined similarly, with the words 'arbitrary subset' replaced with 'countable subset'. Clearly every band is a  -ideal, but the converse is not true in general.

-ideal, but the converse is not true in general.

As with ideals, for every non-empty subset A of E, there exists a smallest band containing that subset, called the band generated by A. A band generated by a singleton is called a principle band.

Disjoint complements

Two elements f,g in a Riesz space E, are said to be disjoint, written  , when

, when  . For any subset A of E, its disjoint complement

. For any subset A of E, its disjoint complement  is defined as the set of all elements in E, that are disjoint to all elements in A. Disjoint complements are always bands, but the converse is not true in general.

is defined as the set of all elements in E, that are disjoint to all elements in A. Disjoint complements are always bands, but the converse is not true in general.

Projection bands

A band B in a Riesz space, is called a projection band, if  , meaning every element f in E, can be written uniquely as a sum of two elements,

, meaning every element f in E, can be written uniquely as a sum of two elements,  , with

, with  and

and  . There then also exists a positive linear idempotent, or projection,

. There then also exists a positive linear idempotent, or projection,  , such that

, such that  .

.

The collection of all projection bands in a Riesz space forms a Boolean algebra. Some spaces do not have non-trivial projection bands (e.g. ![C([0,1])](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/8dbbcbb0e878bab88516ad2b7d27f8e0.png) ), so this Boolean algebra may be trivial.

), so this Boolean algebra may be trivial.

Projection properties

There are numerous projection properties that Riesz spaces may have. A Riesz space is said to have the (principle) projection property if every (principle) band is a projection band.

The so-called main inclusion theorem relates these properties. Super Dedekind completeness implies Dedekind completeness; Dedekind completeness implies both Dedekind  -completeness and the projection property; Both both Dedekind

-completeness and the projection property; Both both Dedekind  -completeness and the projection property separately imply the principle projection property; and the principle projection property implies the Archimedean property.

-completeness and the projection property separately imply the principle projection property; and the principle projection property implies the Archimedean property.

None of the reverse implications hold, but Dedekind  -completeness and the projection property together imply Dedekind completeness.

-completeness and the projection property together imply Dedekind completeness.

Examples

- The space of continuous real valued function on a set X with compact support with the pointwise partial order defined by f ≤ g when f(x) ≤ g(x) for all x in X, is a Riesz space.

Properties

- Riesz spaces are lattice ordered groups

- Every Riesz space is a distributive lattice

References

- Bourbaki, Nicolas; Elements of Mathematics: Integration. Chapters 1–6; ISBN 3-540-41129-1

- Riesz, Frigyes; Sur la décomposition des opérations fonctionelles linéaires , Atti congress. internaz. mathematici (Bologna, 1928) , 3 , Zanichelli (1930) pp. 143–148

- Sobolev, V. I. (2001), "Riesz space", Encyclopædia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-4020-0609-8, http://eom.springer.de/R/r082290.htm

- Zaanen, Adriaan C. (1996), Introduction to Operator Theory in Riesz spaces, Springer, ISBN 3-540-61989-5